The Cash Myth in the Jewellery Business

- Vivek Krishnan

- Dec 13, 2025

- 5 min read

Jewellery Business Series – Episode 2

Jewellery is often described as a cash business. Customers walk in, choose an ornament, and pay upfront.

So why do jewellers — even reputed, high-turnover ones — constantly struggle for liquidity?

The answer lies in a simple but overlooked reality:

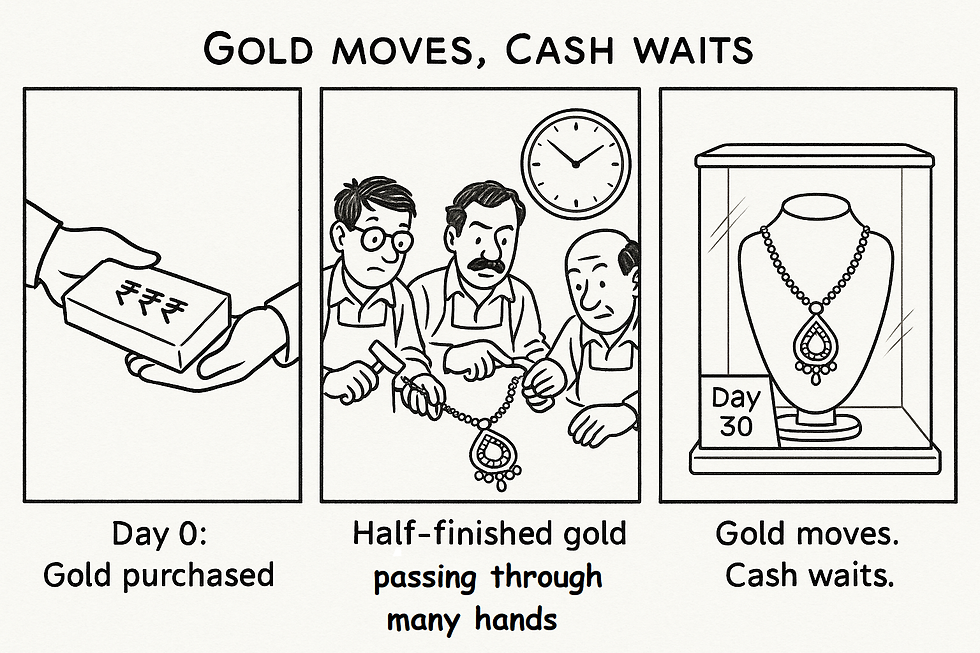

Jewellery may be paid for in cash, but it is never built in cash.

The misunderstanding

When we say “cash business”, we usually mean cash at the counter. But for a jeweller, the billing counter is only the final act of a much longer process.

By the time a customer pays, capital has already been:

committed,

converted,

locked,

and exposed to risk.

Gold Bar → Casting → Polishing → Stone Setting → Finished Ornament

Day 0 Day 5 Day 12 Day 20 Day 30

Where cash really gets stuck

1. Gold is purchased before a customer exists

Gold is not bought after a sale — it is bought in anticipation of one.

Whether through own funds, bullion credit, metal loans, or supplier arrangements, gold is acquired upfront and sits as inventory.

That inventory carries:

full gold value,

price volatility,

and opportunity cost.

👉 Cash is blocked before revenue is even visible.

2. Conversion takes time — and time locks capital

A gold bar does not become an ornament overnight.

It passes through melting, casting, shaping, polishing, stone setting, and finishing — often handled by different specialists.

Typical conversion cycles range from 7 to 30 days, sometimes longer.

During this period:

gold cannot be sold,

cash cannot be recovered,

and price risk continues.

👉 Gold moves through hands, but money stands still.

3. Costs are paid before sale

Karigars don’t wait for customers.

Making charges, advances, and milestone payments are settled before the ornament is sold. Even in “pure cash” retail models, costs run ahead of collections.

4. Value does not always mean liquidity

Jewellery demand is design-sensitive and season-driven.

An ornament may be valuable, hallmarked, and well-crafted — yet remain unsold for 30 to 120 days.

Gold is valuable. Until it sells, it is still illiquid.

5. Exchange transactions create double strain

Old-gold exchange adds another layer.

Old gold is accepted today. New ornaments are delivered later. Melting, valuation, and re-fabrication take time.

In between, capital is tied up on both sides, creating overlapping inventory cycles.

👉 One transaction quietly creates two working-capital locks.

Putting it together

Seen end-to-end, the jewellery business works like this:

Capital is committed before demand

Costs are incurred before sale

Inventory is held before liquidity

Cash arrives only at the very end

Which leads to the central insight:

Jewellery is not a cash business. It is a business where cash arrives only after capital has already worked.

Why this matters — especially to lenders

When these realities are underestimated:

gold loans get stretched,

short-term funding becomes structural,

rollover and barter models emerge,

and stress surfaces sharply during price volatility.

What looks like indiscipline is often misread liquidity timing.

The same business. Two very different lenses.

Aspect | Jeweller’s Reality | Banker’s Expectation | Where the Gap Arises |

Gold purchase | Bought in advance, seasonally | Should convert quickly | Anticipation vs linearity |

Inventory | Held 30–120 days | Expected to rotate fast | Value ≠ liquidity |

Conversion time | 7–30 days | Faster draw–repay cycles | Processing is invisible |

Labour payments | Paid before sale | Assumed post-sale | Debits without credits |

Exchange | Overlapping cycles | Cash-neutral | Temporary double lock |

Sales pattern | Lumpy, event-driven | Steady churn | Seasonality misread |

Unsold designs | Valuable but stuck | Expected liquidation | Design risk ignored |

Price volatility | Affects demand & timing | Seen as added safety | Churn disrupted |

Why bankers expect churn (and why they’re not wrong)

From a banker’s lens:

Gold is highly liquid

Jewellery is paid for in cash

Accounts should show frequent credits and regular repayments

This expectation is logical — but incomplete.

Why churn often doesn’t appear

What account statements don’t clearly show:

time lost in conversion,

inventory locked in designs,

exchange-cycle overlaps,

costs paid ahead of sale,

seasonality distortions,

and price volatility delaying purchases.

As a result:

low churn ≠ low activity

irregular credits ≠ stress

high utilisation ≠ indiscipline

Often, it simply means:

Capital is working — but has not yet returned.

The core misalignment

Bankers measure liquidity through account churn.

Jewellers experience liquidity through inventory movement.

Until this gap is recognised:

limits feel perpetually tight,

GMLs stretch,

rollovers become habits,

and stress surfaces suddenly.

A small billing moment that reveals a bigger truth

A colleague recently narrated an experience many families would recognise.

While exchanging old ornaments for new ones at a reputed jeweller, she noticed:

a 3% making-charge deduction on old gold, and

a 0.5% “discount” on the new ornament.

Net result? Despite a gold-for-gold exchange, she was worse off.

When questioned, part of the deduction was reversed.

The jeweller’s candid remark:

“Most families don’t notice this in the moment.”

This is not about wrongdoing. It is about hidden economics.

What actually happens during exchange

Old gold:

has uncertain purity,

suffers melting loss,

needs refining and job-work,

and takes time before reuse.

New ornaments:

recover labour, wastage, and overheads,

reflect inventory risk already absorbed,

fund design obsolescence.

What looks like a simple swap is actually:

Two separate economic transactions stitched together at the billing counter.

Someone must finance the gap.

Why working capital is unavoidable

Despite cash inflows, jewellers face:

time mismatch between receipt and reuse,

cost mismatch between scrap and ornament,

price risk during holding,

operational float across the supply chain.

Gold may be liquid. Jewellery is not.

Working capital bridges the transformation.

Industry practices (illustrative)

Practice area | Common approaches |

Old gold exchange | 1–4% deductions, purity haircut |

New pricing | Making charges, wastage recovery |

Adjustments | Partial offsets framed as discounts |

Disclosure | Verbal, moment-dependent |

Margin recovery | Embedded, not explicit |

These practices are not uniform — but they are widespread.

A banker’s checklist: reading jewellery accounts beyond churn

✅ Normal (do not overreact)

High inventory with moderate churn

High utilisation of limits

Lumpy credits

Exchange-heavy festive transactions

Embedded making-charge recovery

Rolling gold loans due to timing mismatch

⚠️ Grey zone (ask deeper questions)

Thin margins despite turnover

Inventory high vs reported sales

Discretionary exchange reversals

Frequent short-term funding changes

Ambiguous wholesale claims

🚩 Red flags

Entrusted/job-work gold shown as owned stock

Sales routed outside operative accounts

Gold sold but not replenished in GMLs

Borrowings rising without sales growth

Inconsistent inventory valuations

Misclassified business models

The takeaway for bankers

In jewellery lending, liquidity must be read through process — not just the passbook.

Account churn tells when cash moved. Inventory movement explains why it hasn’t returned yet.

Good underwriting reconciles both.

Disclaimer:

This article reflects personal views formed through professional experience, industry observation, and public information. It does not constitute investment advice, policy commentary, or an institutional position, nor does it refer to any specific bank, client, or transaction.

Comments